11. Killing with Kindness? The Challenges of Conservation and Access for Living Matter

- Marcia Reed

One of the most difficult moments in the life of an artwork can be when it enters an institution. In this author’s experience, private collectors tend not to over-conserve, most often erring on the side of passive storage. Some of the most discerning collectors simply wish to appreciate and enjoy their works of art on a daily basis, which means that the works are, for instance, displayed for lengthy periods in too much light. Such collectors enjoy living with art, and they don’t worry about extending its life or preserving works in perpetuity. Indeed, it could seem a bit pretentious to assume responsibility for creating an eternal life for a work of art.

Collecting plays out very differently with libraries, archives, and museums, sometimes taking on the worst senses of “institutionalization.” While early works on paper can behave well for centuries, more recent ones, particularly twentieth-century avant-garde and Fluxus works, present problems. Indeed, many were created specifically to challenge institutional authority, to act out, and were thus intentionally not made to last. They warp, wrinkle, leak, ooze, or explode as they age. These artworks were created to be in an extended state of process. It is a given that they will deteriorate, and maybe completely disappear, as is the case with early photocopies and faxes. They exist as documents as much as art. Most significantly, they’re made to be experienced and handled rather than entombed like untouchable treasures in cases. I have thought more than once that if something unpleasant happened to certain works, it might even please the artist, who may no longer be with us but whose work is still actively talking back. The incorporation of living materials is especially sympathetic to creating art that is not static, but rather notable for its tendencies to change and decay, effectively as if it were a living organism.

The Getty Research Institute (GRI) special collections include rare and unique works that document the history of art. Up to the twentieth century, they are mostly works on paper. But modern and contemporary artists have occasionally included food, plants, or even dead animals in their works. When considering objects in the GRI’s special collections that are made from living matter, it is clear that references to both their initial status as well as to their present, now-changed condition are crucial to their meaning and to an appropriate—that is, direct and unmediated—experience and appreciation of the work. For both historical documentation and surrogate viewing, photography and digitization are remarkably helpful, often revealing more information than the naked eye can discern. And documentation of how these objects are stored, conserved, and accessed is also critical to their comprehension.

The important questions include: Is it possible to preserve the work responsibly without interfering with the artist’s intent that it age and/or disintegrate? Can it still have a life? And should it? Once works become institutional assets, must we preserve them as typical institutional assets if that counters what the artists intended? If a work is made to be handled and we only show it behind glass or in a case, are we denying the right of the work to exist and function as the artist wished? In certain cases, at least one of these issues can be simple. For instance, if an artist’s book is made to be read, then we must provide a way to do that at some point, thus allowing the crucial experience of the book’s materiality to take place. Dieter Roth’s books, for example, have not been read so much as simply viewed as book sculptures, but they are filled with his words, his poetry. To deny access to the texts fails to acknowledge a critical facet of the work, which is the interactions of words and images in the context of Roth’s selections of specific materials.

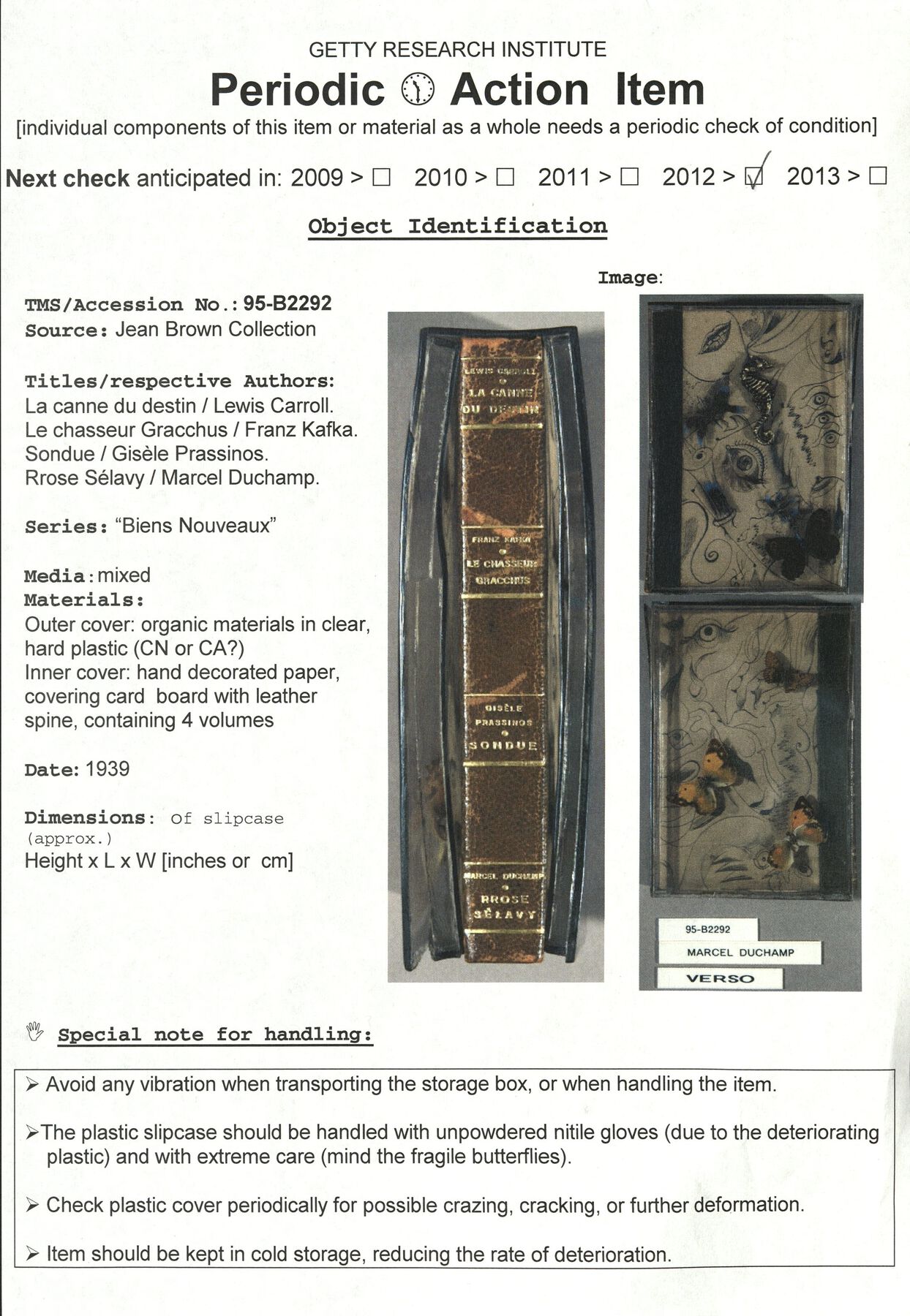

Signature characteristics of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art include such intricately interwoven presentations of texts and images, for which, it should be stressed, reading is often crucial. A touchstone of the genre is Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box (1934, fig. 11.1), filled with quasi-archival documents that present an explication of his Large Glass (1915–23). Like Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase), produced in multiple editions as a box or valise that presents miniatures of his works, the Green Box requires firsthand access to touch and to read. This becomes difficult when these are designated masterpieces—significant works by a major artist. In Mexico City on the last day of the “Living Matter” conference, attendees viewed works by Duchamp, including the Green Box, in glass cases at Museo Jumex as part of the exhibition Appearance Stripped Bare (). The boxes were shown in galleries together with works by Jeff Koons, and the juxtaposition was telling. The exhibition presented Duchamp’s boxes in a state of embalmed inaccessibility, like closed books. The implicit denial that they are made to be unpacked, handled, and read took away their aura and retracted their power. Meanwhile, Koons’s brightly colored paintings and shiny sculptures grabbed visitors’ immediate attention. Duchamp smiled wisely and somehow knowingly out from the vintage photographs and film in the show.

Figure 11.1

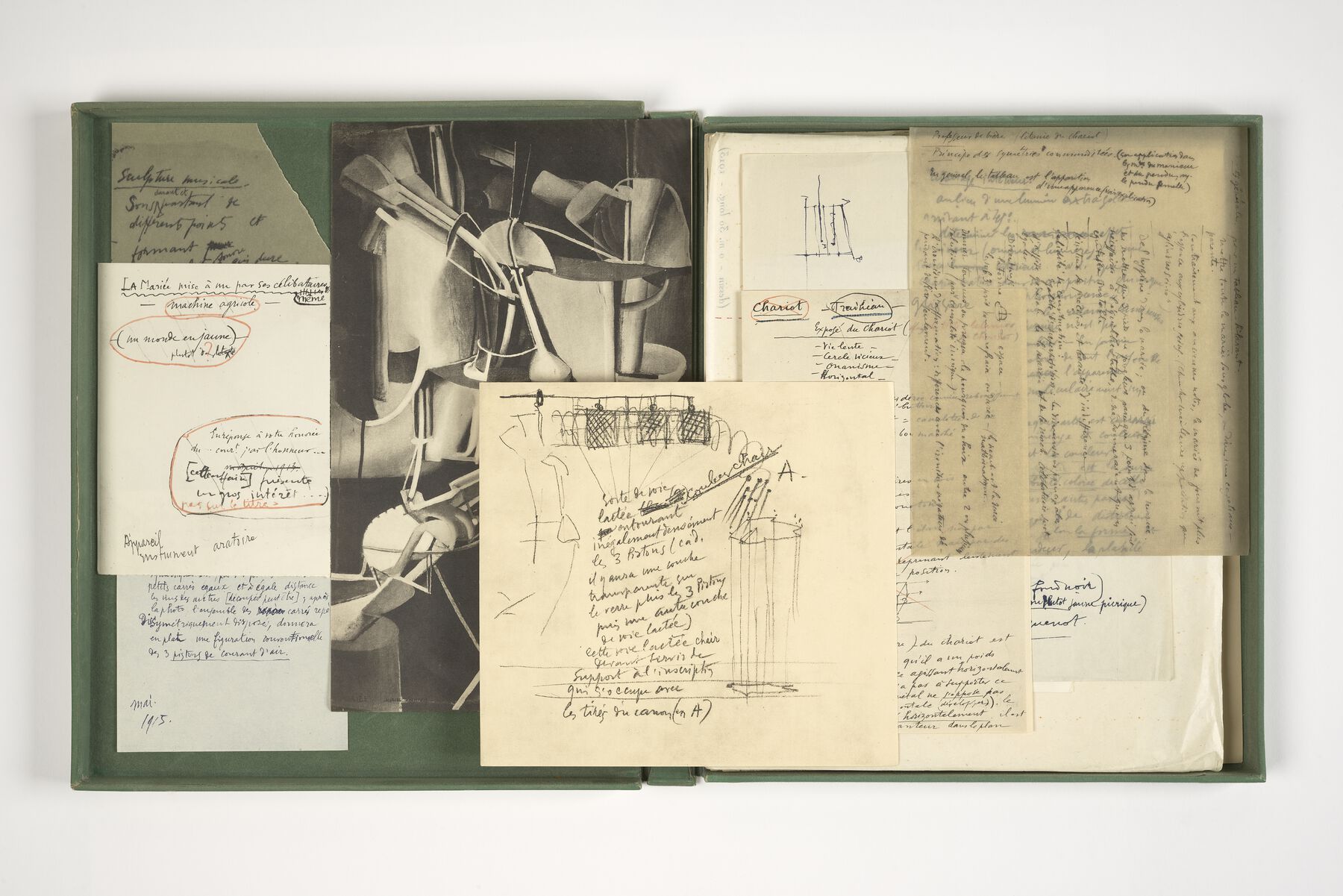

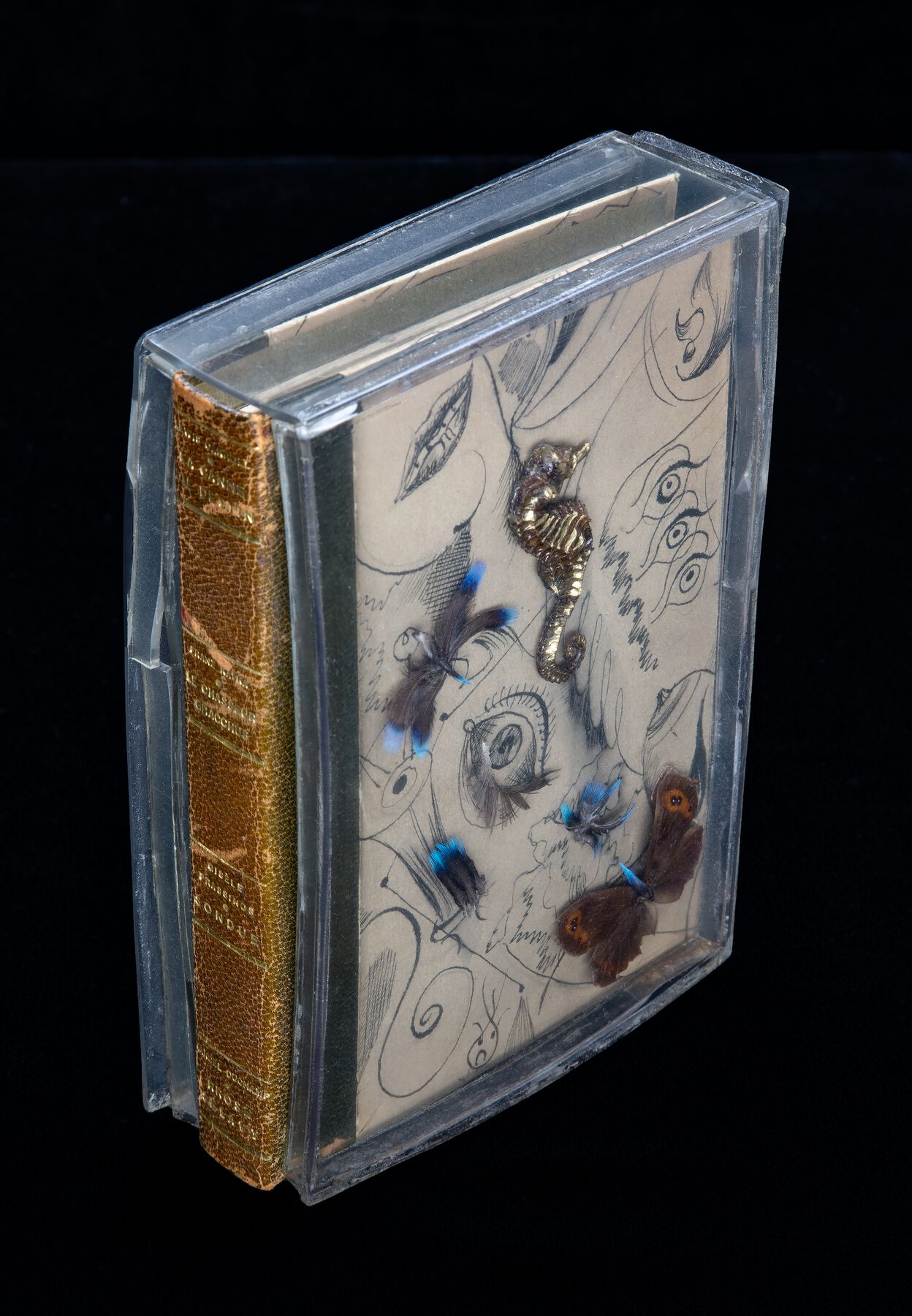

Figure 11.1At the GRI, one of our first experiences with making major conservation decisions regarding living matter came with the acquisition of the Jean Brown Collection. Although Brown is well known today as a collector of Fluxus works, in collaboration with her husband, Leonard, she also collected an extraordinary group of Dada and Surrealist editions in the late 1950s and 1960s. The Browns had especially complete holdings of Duchamp’s signature boxes and publications. Their Dada, Surrealist, and Fluxus collections were acquired by the GRI in 1985, and the first encounter with living matter concerned a small case of books (fig. 11.2, fig. 11.3). This Surrealist cellulose acetate case filled with butterflies, feathers, a seahorse, and eyelashes arrived with the Jean Brown Collection in a state of serious deterioration. Attributed to Duchamp and André Masson, it dates from around 1939. A Surrealist object in itself, the book case holds 1939 editions of four literary classics published by in Paris by Guy Lévis Mano under his GLM imprint in the series Biens Nouveaux. The small, elegant books are Lewis Carroll’s La Canne du destin (The Walking Stick), Franz Kafka’s La chasseur Gracchus (Gracchus, the Hunter), Gisèle Prassinos’s Sondue, and Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy. In the 1930s and 1940s, GLM published hundreds of illustrated Surrealist editions in these sorts of tastefully designed paperbound quartos. While the Surrealists often portrayed bizarre variations on living bodies—contorted, dismembered, part animal, part insect—they did not often actually employ living matter in their art. (The major exception is of course Meret Oppenheim’s Object [1936], the fur-covered cup and saucer.) To date, no documentation has been found concerning the fabrication of this unique book case, except for an unknown dealer’s description. Possibly it was designed by Duchamp’s companion at this time, the book designer and binder Mary Reynolds, in collaboration with Masson, who drew the figures in ink on the cardboard chemise. The box serves as an overlay for the drawings on the chemise. They are created as an ensemble, to be enjoyed visually while reading the deliberately strange selection of texts stored within.

Figure 11.2

Figure 11.2By the mid-1980s, when the GRI acquired the Jean Brown Collection, the case was yellowed and warped, partly split at the seams. The gilded seahorse, butterflies, and feathers were desiccating. This hauntingly beautiful and truly surreal book-object, evoking a dreamlike otherworld and the perfect enclosure for its fantastical literary works, has been exhibited once as of this writing, in the 1994 GRI exhibition Sites of Surrealist Collaboration. It was displayed in a wall vitrine with a black velvet curtain to protect it from sustained direct light.

In the years before the new Getty Center was built, the GRI’s collections storage building also housed the Getty Conservation Institute. One of the GCI scientists, Jim Druzik, had considerable experience with the effects of lighting and museum display. Happening by one day, he took an interest in the case and its books, offering to assess it and make recommendations. In collaboration with a GRI conservator, the case was stabilized and squared up slightly so that the books could fit into it again, although they are now stored separately with instructions for unpacking, storage, and use so as to limit abrasion and handling of both the books and particularly the case, which requires very limited handling and no sudden movement. The surface was lightly cleaned, since it had accumulated dirt. Unbeknownst to us, Druzik was a butterfly collector. He identified the butterfly species and asked whether we wanted to replace them. He brought in a drawer of very similar specimens for us to select from if we wished. But the decision was immediately obvious: to replace the butterflies seemed like unacceptable cosmetic surgery. It was a suggestion to which perhaps Duchamp would have responded with his familiar mysterious smile, but at the time, it did not seem an appropriate option. With objects such as these, there is an ongoing life. It should be tended to with care, but the process should not be interfered with.

A coda to this past decision is that the butterfly wings are now desiccating further, fading and turning to powder. As such objects age and change, conservators and curators may want to reconsider whether to enhance (meaning, restore) the artistic qualities or to continue to preserve and stabilize the objects as well as they can. Almost inevitably they will continue to change.

In addition to this unique work, Duchamp also created numerous multiples—a new category in the twentieth century, a kind of small-scale artistic mass production. Duchamp himself was an early adopter of this format because it worked well in the context of his readymades. Although multiples begin their lives produced in groups (hence the term) of identical or very similar objects, as they are acquired by collectors or institutions, they proceed to experience different histories. Their residence in various locations with different conditions of housing and display results in changes in their appearance. Plastic, itself a potentially unstable material, is often used in multiples, sometimes as a container, and sometimes combined with living matter, as in some Fluxus boxes. Post-avant-garde artists’ books, multiples, and objects with text and images often use plastic for transparent enclosures, for instance as sleeves that become the leaves of a book.

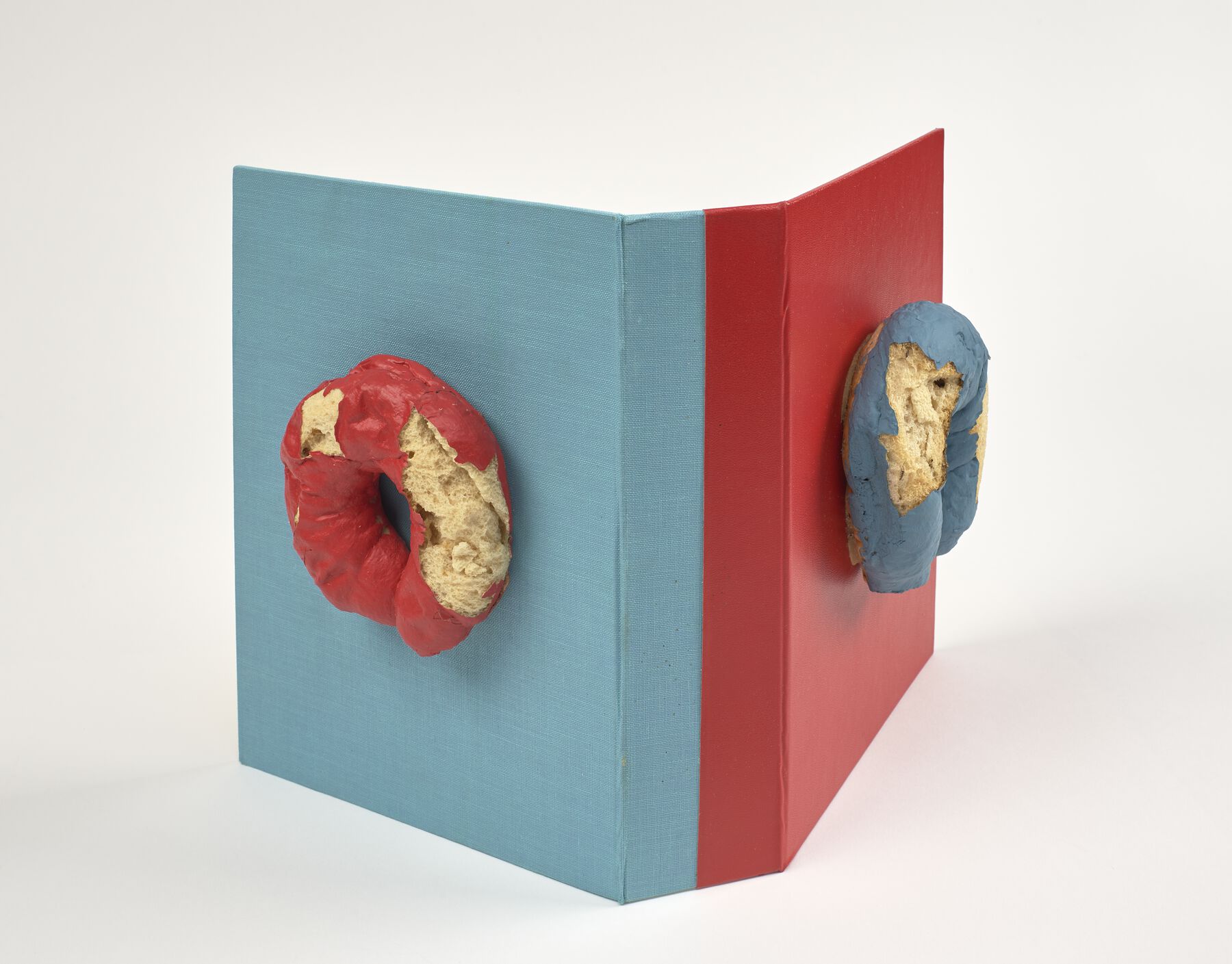

Jean Brown was fascinated by the works of Dieter Roth and acquired more than fifty volumes directly from him. She particularly appreciated Roth’s experiments with book design and publishing formats, such as his combination of traditional printing techniques with contemporary materials that are far more unstable than the papers that bookmakers used for centuries. Brown had at least two copies of the special edition of Roth’s Bok 3c: Wiederkonstruktion des Buches aus dem Verlag Forlag Ed (Reconstruction of the Book from the Verlag Forlag Ed., 1961/1971, fig. 11.4), which has a separate slipcover embellished by either painted bagels or croissants. The GRI has bagels; the Museum of Modern Art, New York, has croissants (, 29). Here, the question is whether to restore the sections of the bagels that have crumbled. So far the bagels are slightly deteriorated, and the crumbs have been carefully preserved, somewhat sympathetically collected in a small bag; because of their fragility, the covers receive only supervised use.

Figure 11.4

Figure 11.4The GRI holds five different copies of Roth’s special editions of Poetrie. Two are printed on plastic pages. The pages of one are filled with urine, which we know with certainty because of its smell. Another edition of Poetrie is filled with either cheese or pudding. The latter has not been tested because we are hesitant to disturb its apparent equilibrium. The evocative plastic pages of Roth’s poems wrinkle like skin. Because they have a tendency to stick together, they have been interleaved, as is commonly done with freshly produced prints.1 A plastic spine supports the book; the plastic pages pucker. When standing up, the volumes lean uncertainly, like elderly people.

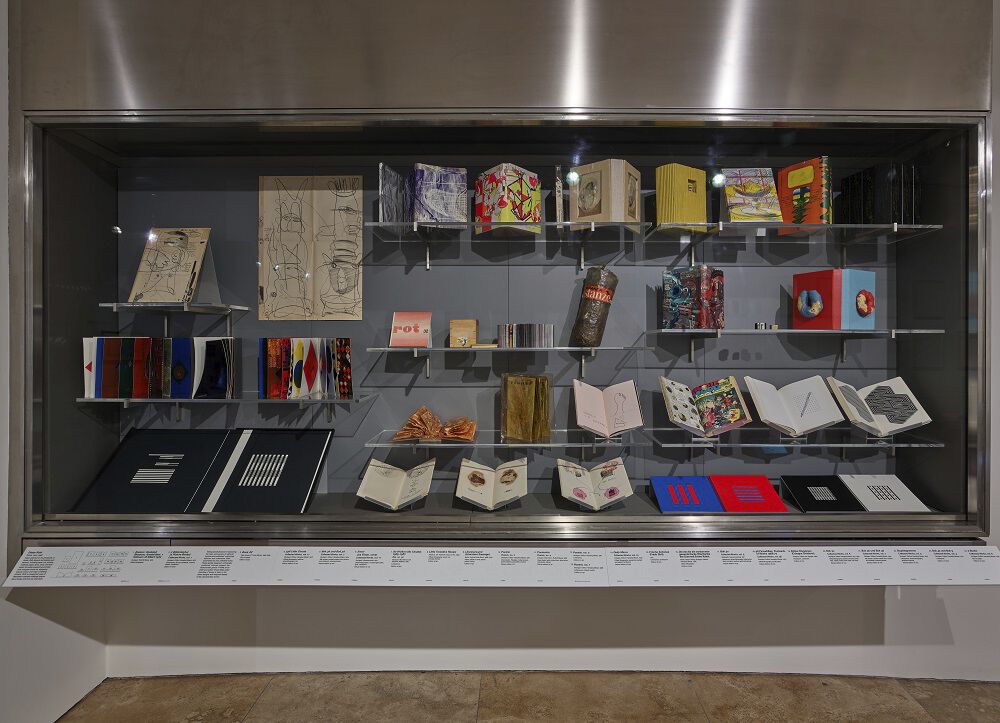

Almost forty of Roth’s variations on book structure were displayed in the 2018 GRI exhibition Artists and Their Books / Books and Their Artists (; fig. 11.5). The volumes filled with living matter absolutely stole the show. It seems that living matter resonates especially in artists’ books such as Roth’s, which themselves are visual references to physicality. The editions of Roth’s Poetrie (with variant spellings: Poemetrie, Poeterei) were shown, all embellished differently by him with watercolors or ink, or versions in which the poems are printed on plastic leaves filled with urine or cheese (). It seems that Roth cannot make the same book twice. Each is an inspired variant performance to be viewed and read differently. But my concerns at the time involved touch specifically. Handling the books is important to their concept, but the plastic is fragile, and the printed words of the poems could stick together or fall off the pages. And what about smell? Is the intentionally strong, unpleasant smell of the urine book part of the experience of reading it? At the time of the exhibition, these issues remained unaddressed. Viewers were not permitted to touch the books on display, and the smell of the urine book did not penetrate the glass case.

Figure 11.5

Figure 11.5Another edition of Roth’s poems, also from the Jean Brown Collection, had an inserted slice of mutton. When the collection was received, conservators took the mutton out of the book (noting the page it had been on) and placed it in a separate housing because it was staining the pages. No doubt this removal was done with good intentions; mutton has no place in a proper book. However, to see the mutton stain as a problem to be rectified, rather than a deliberate intervention by Roth, is a misunderstanding of the work. The conservation treatment interferes with the deliberate insertion of a smelly piece of meat intended to spread a stain on the pages. Roth’s essential idea was precisely that the mutton’s presence is part of the life of this book. Can institutions justifiably counter an artist’s intentions?

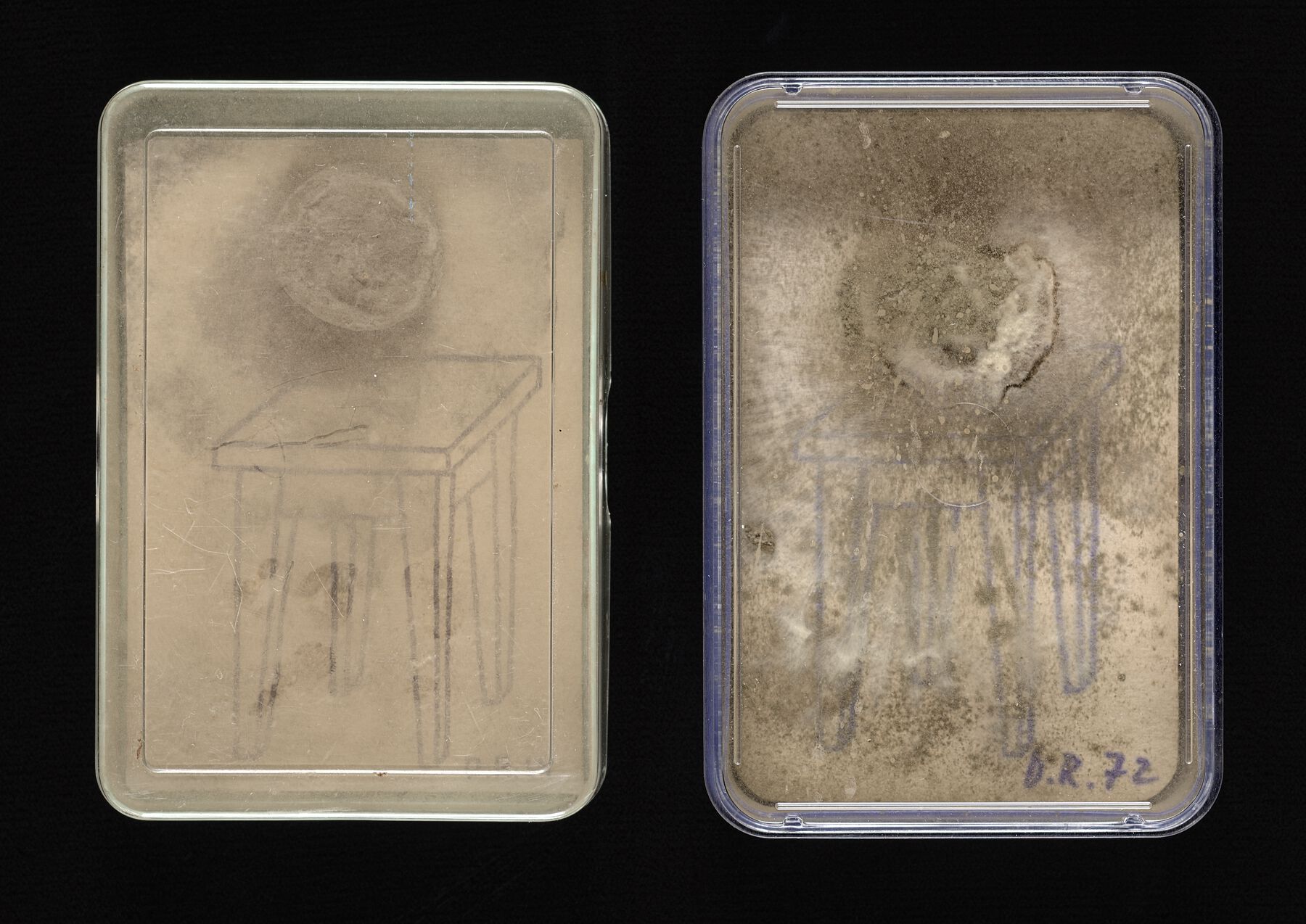

Compared to such tour-de-force gestures, Roth’s editioned multiple Taschenzimmer (Pocket-Room, 1969/1972, fig. 11.6) always struck me as an engaging piece that conceives a simple life for an artwork. It is an exhibition in a modest container—a cardboard box that opens to show a print of a table with a small piece of banana peel tacked on. Of the two in the GRI collection, one is quite moldy, and the other is dried out. One box has no lid and is possibly a variant edition. Roth’s deployment of the banana slice has to be intentional. Who is not familiar with the life cycle of a banana, and the fruit’s frequent use in jokes? Fortunately, several other versions in institutional collections are well documented. All have aged differently according to storage conditions, illustrating how resonant it is to use living matter in an edition in which initially identical works go out into the world and change according to their situations. Should the decayed fruit and mold in Taschenzimmer be cleaned up? Again, this would seem to contradict Roth’s intent. Better to just let its aging process proceed and make sure that the mold doesn’t migrate.

Figure 11.6

Figure 11.6Like Roth’s books, many Fluxus works are collections of seemingly miscellaneous things drawn from life, significantly not composed so as to be immovable. Domestically staged and deliberately not monumentalizing, they present an accessible atmosphere of informality. But they are also cheaply made and fragile. For instance the hinges on the brittle 1960s-era plastic Fluxus boxes break. The plastic becomes cloudy. To engage with the work, you must take objects out of the boxes, some of which include found objects from nature, such as branches, nuts, pine cones, scat, and bones. Elements in many privately owned boxes have gone missing. How should they be viewed or handled, and how much is too much manipulation? Does lack of access isolate and silence them? Viewing in vitrines effectively suffocates these works. It shuts them up and cuts off the essential personal connection. Yet how can these boxes be viewed in an appropriately informal way if this very activity consumes them? Can the original artists or owners restore, or reconstitute, new works, as Barbara Moore did in her ReFlux Editions?2 Or do original works become artistic monuments and historical markers when they are acquired by institutions or collectors, arrested in time, needing to be stabilized and preserved but withdrawn from their intended lives? Does adding reproductions of missing elements constitute restitution of a new generation of objects for another lifetime, or inauthenticity? Perhaps with open editions (print or multiple editions without a specific number or date), that’s really okay.

One Fluxus work by George Maciunas most certainly will not be considered for reproduction. In a glass jar, not plastic, the GRI’s Fluxmouse no. 1 (1973, fig. 11.7) is preserved like a specimen in a natural history museum. Murdered by Maciunas, imprisoned in a jar, and packed in an archival box, this small dead animal is presently shelved in a dark vault. Full disclosure: conservators monitor this work, and have added liquid, so there has been some intervention even here. One could observe that although Fluxus artists did make works that include living matter, the mouse is significant in large part because it is no longer living. It has become art.

Figure 11.7

Figure 11.7About fifteen years ago, there was a true emergency, actually a confined but messy explosion in Fluxus artist and composer Benjamin Patterson’s tackle box Hooked (1980, fig. 11.8). The lid of the box swings up and opens out to reveal several shelves; each compartment holds an everyday object with a hook in it. It is a complex work with many parts, some of them moving. The box had been stored in an archival banker’s box, examined and stabilized by a GRI objects conservator. But when the box was brought out of storage it was smelly, and a sticky substance was oozing: a very old can of sardines in tomato sauce had exploded. Canned goods do have shelf lives, and this one had expired years ago. The conservator cleaned up the mess and assessed whether any of the other pieces were damaged; they weren’t. Pictures were taken; documentation was noted. But what to do now about the integrity of the work? Keep the old can, but not in the tackle box? The conservator did locate a very similar sardine can online, and purchased it. As with the Surrealist butterflies previously mentioned, should the can be replaced? Even if that would only start the clock for another explosion in the future?

Figure 11.8

Figure 11.8Patterson had formerly worked as a librarian at the New York Public Library’s Performing Arts branch, and so he was familiar with archives and library practices. He was living in Wiesbaden, Germany, and we were in occasional contact. We got in touch to ask about his intention for the work, but when asked what he would do, Patterson responded, “I don’t care. It’s yours now.” Apparently he possibly considered the old sardine can garbage to be thrown away. Speaking for other Fluxus artists, most of whom had died by then, Patterson said he thought they would accept that their works deteriorate, and so it would be inappropriate to re-create a work that was intended to have a limited life span. This reinforced a principle of stewardship for the GRI’s Fluxus and related collections—namely, that Fluxus means change. The materials were selected by the artists with change as a given. Stabilizing the object and impeding this process denies the spirit of the works, which in most cases are still living long after their makers have died.

In case you are wondering, the old sardine can was retained (fig. 11.9); the newly purchased can, its near twin, was emptied but weighted similarly and placed in the tackle box.

Figure 11.9

Figure 11.9How living matter is dealt with is finally also a curator’s and conservator’s ethical decision; it is a matter of respect, not only for the artist, but for all living matter. One of the most disturbing moments in my curatorial career involved finding in the archive of Los Angeles photographer Charles Brittin a small body part belonging to a woman who immolated herself during an LA civil rights protest in the 1960s. Observing city workers cleaning up, the artist saved what he could, boxed it, and forgot about it. It had been dutifully catalogued when I discovered it in the GRI special collections. Realizing this archival resting place was not respectful to the woman’s memory, I worked with our legal counsel to place the fragment in the Los Angeles city morgue, from whence it would be returned to the family.

This is an extreme example but points to the truth that conservation of media should always return to and respect not just the artist’s concept, but also the object itself. When we can, we do ask living artists for advice. But not all creators are still with us, and so the looming question concerns appropriate care and treatment as the life cycle of the work spirals onward. The answer: we talk, we test, and we talk some more. Collaborative communication among artists, conservators, curators, and scientists informs our stewardship of our collections.

Notes

They are interleaved with nonwoven polyester and thin microchamber boards containing zeolites. These act as molecular traps to neutralize acids, pollutants, and other harmful by-products of deterioration. Thanks to Rachel Rivenc, GRI head of conservation, for this information. ↩︎

ReFlux Editions was founded by Barbara Moore, a close associate of Fluxus leader George Maciunas, as a way to continue publication of Fluxus multiples, keeping them indefinitely in print. The works are collated from original vintage printed matter from Maciunas or his estate. The plastic boxes are either vintage or from original sources. See “ReFlux Editions at Printed Matter, Inc.,” e-flux, March 26, 2002, https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/43512/reflux-editions-at-printed-matter-inc/. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Gioni 2019

- Gioni, Massimiliano, ed. 2019. Appearance Stripped Bare: Desire and the Object in the Work of Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons, Even. London: Phaidon.

- Reed and Phillips 2018

- Reed, Marcia, and Glenn Phillips, eds. 2018. Artists and Their Books / Books and Their Artists. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

- Roth 1967–68

- Roth, Dieter. 1967–68. Poeterei 3/4: Doppelnummer der Halfjahresschrift für Poesie und Poetrie. Stuttgart, Germany: Edition H. Mayer.

- Suzuki 2013

- Suzuki, Sarah. 2013. Wait, Later This Will Be Nothing: Editions by Dieter Roth. New York: Museum of Modern Art.