22. Living Matter: Research as Creative Process

- Gabriel de la Mora

On June 5, 2019, I gave this presentation at the “Living Matter” symposium, where the discussions centered on the challenges involved in the conservation of contemporary works of art created with biological materials. I will begin by saying this: I believe that just as matter occupies a place in space, has mass, and endures or transforms over time, research into the conservation of the materials used in an artist’s production is indispensable to the artist’s career or artwork. Thanks to this invitation, I was able to reflect on the exact moment when I became aware of the inevitability of decay of the organic elements in a work of art.

Consideration of living or organic matter has been present in my work as an artist from the start of my career, and perhaps since my youth. I recall an anecdote from my childhood: I was at my family home in the city of Colima, Mexico. One morning I took two clear drinking glasses from the kitchen. I filled one with water from the water faucet, and I filled the other with clear alcohol. I went to the pond in the garden and took out two fish that looked as much alike as possible. I held one in each hand about ten centimeters from the liquid in each glass, and I dropped them both into the glasses at the same time. The fish that fell into the water swam easily, while the other twisted and contorted until, a few seconds later, it was motionless, lifeless. Within my capabilities at that age, I was able to conclude that, in both glasses, although the fish and the liquids looked the same, they were actually different; in one, life continued, and the other held only death.

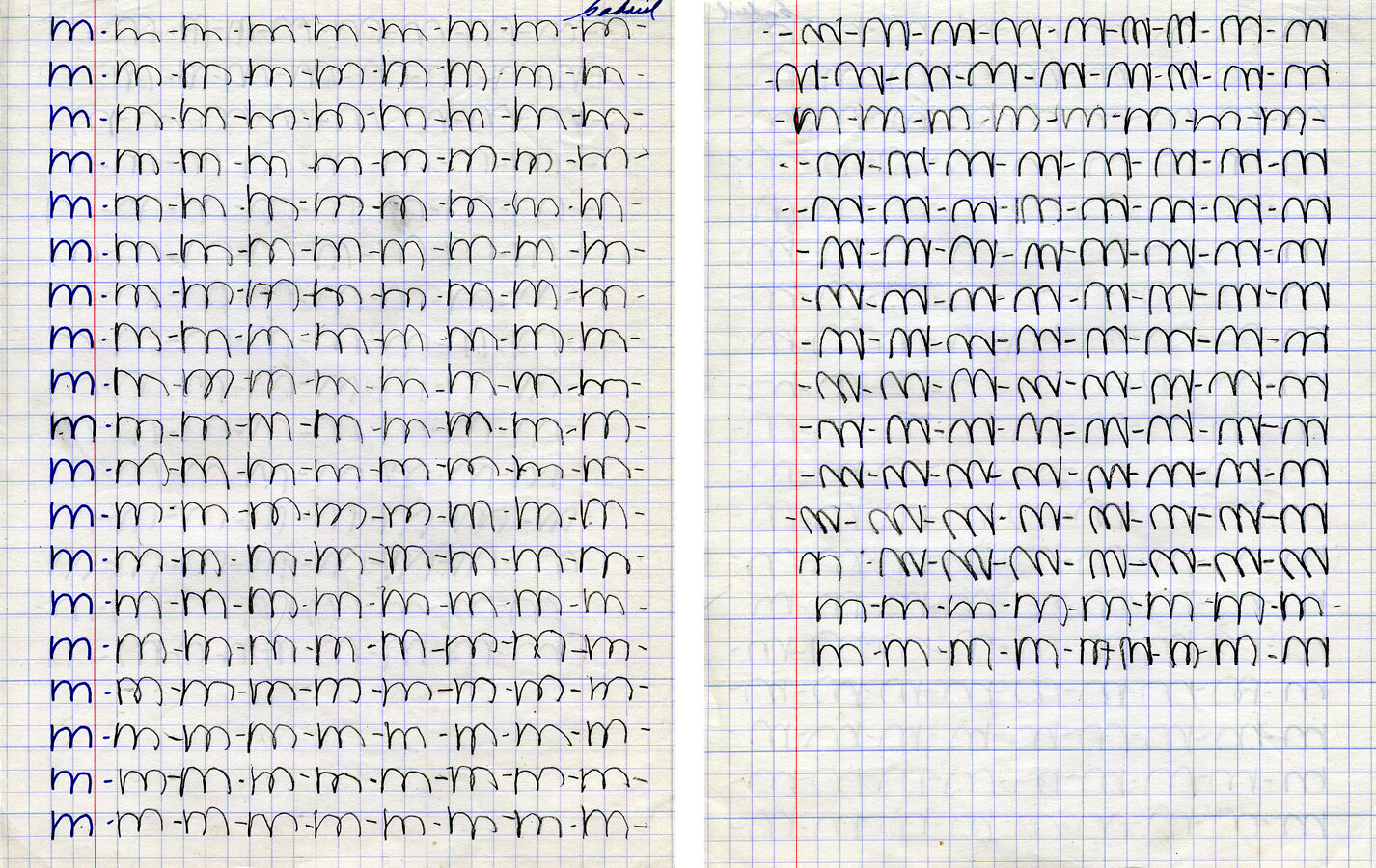

I was drawing before I spoke or wrote, and drawing has always been my best form of expression toward the outside world. I was a child who discovered his environment through questions, experiments, observations (fig. 22.1). I consider this the background to the importance of living matter and research in my creative process. From the perspective of the practice of art, now that I am an adult, that youthful experimentation has led to this type of question: When does an artist begin to be an artist? Are they born an artist, or do they become one when they pursue studies in the visual arts? Or at the moment when they decide to devote themselves to art? Should art be eternal, or will it have continual changes? Will all works of art disappear in the end?

Figure 22.1

Figure 22.1I studied architecture and practiced it for five years, until August 1996, when I exchanged architecture for art. Since the beginning of my career as an artist, I began to experiment with different found materials, mostly discarded items such as latex, feathers, hair, eggshells, and many others. Since then I have enjoyed experimenting with different material elements, and that is why I always conduct a large number of tests to see which materials are ideal for the piece I am creating. All the materials present in my work, besides functioning as containers of stories, memories, or customs, are repeated tests of the durability and resistance of matter. The leap from the two-dimensionality of drawing to the texture and three-dimensionality of all those materials has been the perfect field for experimentation, as I have moved from the simplicity of direct drawing on a support to the complexity of schematization, consolidation, construction, and assembly of pieces with increasingly complex materials.

This process of trial-error-trial-result entailed in my creations has led me to not only posit many questions, but seek solutions that allow me to continue using all the materials I want in building my body of artwork. When answered, these inquiries have become an essential element of my work and have opened doors to material adventures of ever greater complexity.

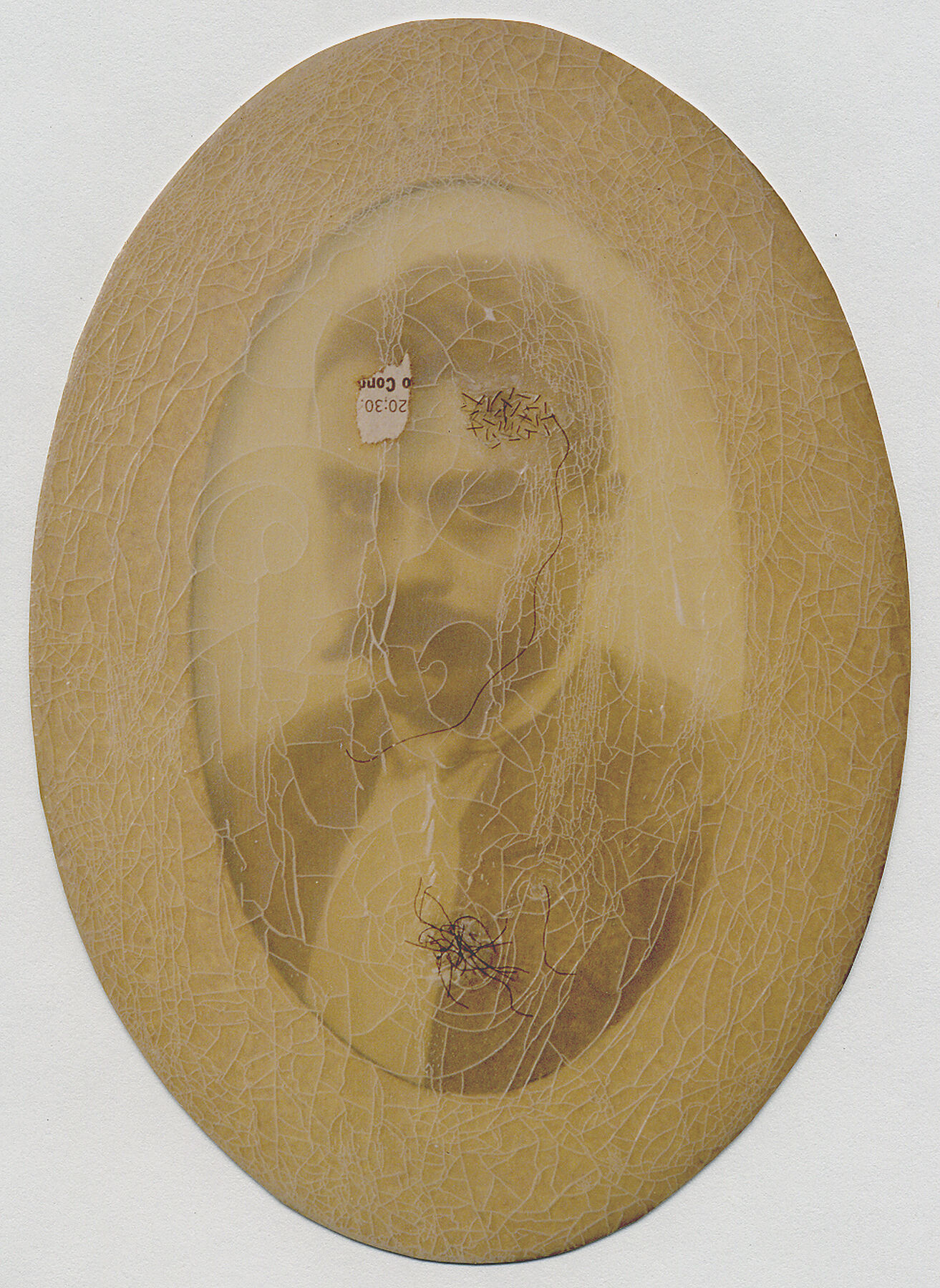

At some point in my creative processes, I try to seek the advice of conservators, because experience has taught me how fundamental it is to have the counsel of experts. To a large extent,my early works were either destroyed or disappeared over time, leaving only the photographic record and some negatives to speak of their existence, which showed me the importance of risk control, conservation, and restoration of the materials used in the art world (fig. 22.2).

Figure 22.2

Figure 22.2When I saw that many of my early works disappeared with the passing of time, I devoted myself to finding someone to constructively accompany me in my explorations and inquiries into the durability of certain materials, for instance the types of adhesives and compounds I should use so that the works would remain as intact as possible for as long as possible. That search led to me working hand in hand with a great conservator in Mexico City, to whom I will always be grateful for providing me with that expert support. This collaboration created countless possibilities for exploration, experimentation, and improvement in my processes. Based on this experience, I began to document as best I could, from the conception of an idea through the entire process of creation, the behavior of the finished pieces over time, and the different environmental conditions that each one underwent as it moved from the studio to the museum, the private collection, or the art gallery.

When I was young, I had the naive belief that art was obliged to survive intact over time. Now, due to all the experience I have gained over more than twenty years of work, I can accept that eventually, after many, many transformations and material changes, everything will disappear. I have learned that there are even pieces whose manifest existence includes, per se, the fact that they will gradually vanish over time, such as the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century photographic images that I have worked with. One example is Fotografía intervenida (Intervened Photography, 2008–ongoing), a series involving faded daguerreotypes, water-damaged photographs, first-generation vintage photographs, and destroyed, semi-destroyed, or exposed negatives. This small collection was classified by subject, source, period of origin, and state of conservation. The photograph—as a technological development that made a faithful record of reality possible—gradually becomes an archive of absences, of the invisible and the phantasmagorical, that creates no certainty and even asks how reliable an image can be, even if it is generated by a machine rather than a human being. The pieces have been severely affected by time. The images are about to disappear given their exposure to sunlight, and that disappearance represents the birth of a monochrome, resulting from a process in which the artist has no influence at all beyond merely drawing attention to something. In Fotografía intervenida the alteration to the pieces begins with the detachment of partial and random fragments of an image. Sometimes I only cut a millimeter off the edge at a time, and continue until I reach the center of the print. Or I simply print negatives that have been accidentally ruined by floods or humidity.

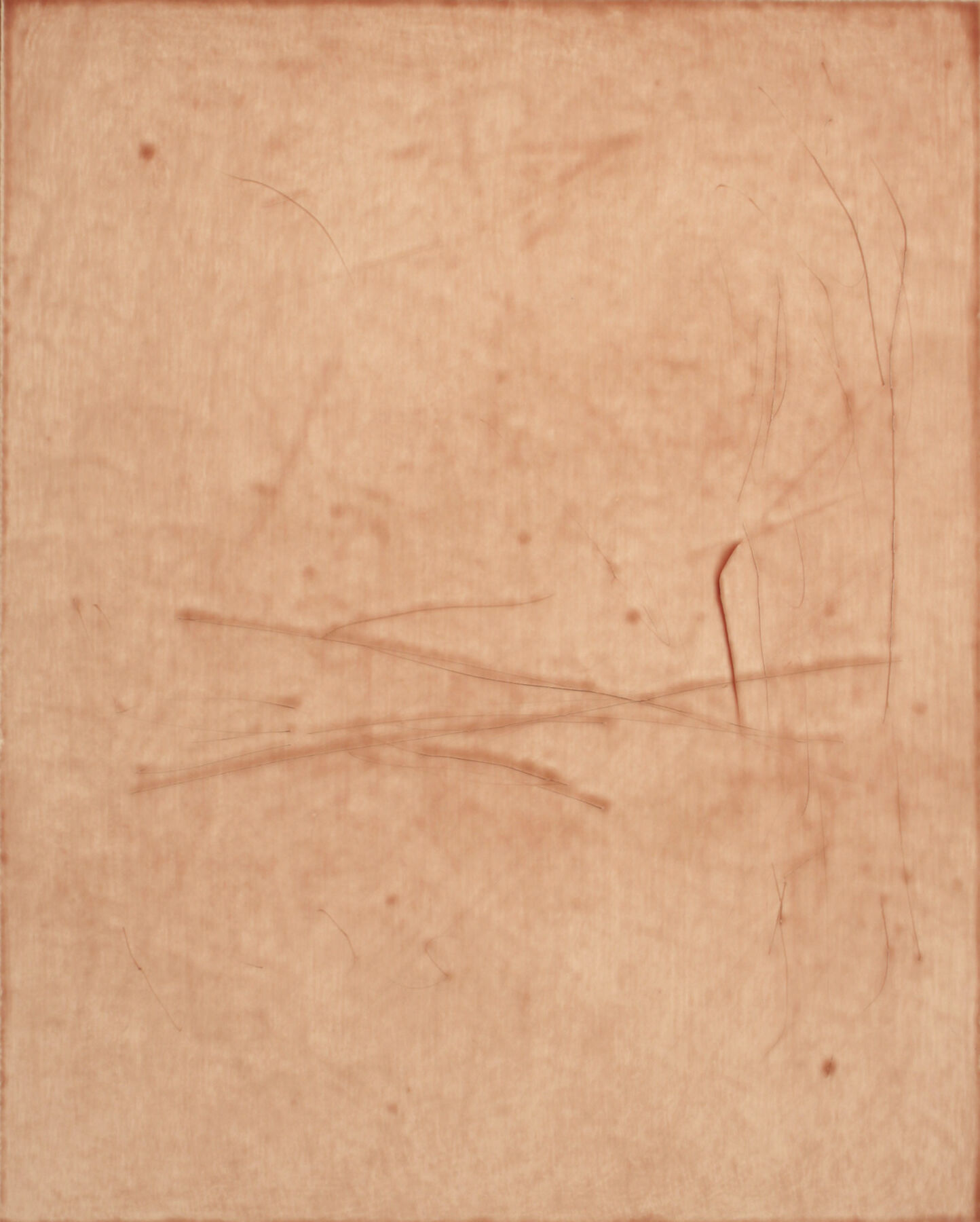

However, I think that all works change, and even if a work is destroyed, it will continue to be the same work, since art does not vanish; it only changes. If a piece breaks, it exists as the same piece, only broken. It simply changes its existence through conditions, its character, time itself. The piece will be in continual evolution. That is the immanent of the permanent. There is a series in which I decided to use my blood (fig. 22.3), which in addition to containing energy, contains my genetic information. I diluted it in acrylic varnish and applied it to a cloth in various layers, perhaps thereby creating my first monochromes. Some time later, a collector who had bought one of these contacted me to report that although the work was not in direct sunlight, it had lost almost all its color after several years. This made me think that the work remains the same work even when it has lost color, because the genetic information is still there. Even though light or UV rays made the color disappear, the work continues to exist as such. I explained this to the collector and told him I was willing to take the piece back in exchange for something else. He asked me about the final destination of the piece he would be returning, and I told him I would keep it as part of the collection. On hearing this, the collector decided to keep it because he still liked it a lot—he was just worried about the color. In fact, from my perspective, the piece could not be remade, or discarded, or even less conserved and restored, its color brought back by reapplying diluted blood. The piece continues to be the same piece, only different, changing in some way as everything changes over time. This experience also supports the premise that Willy Kautz used for the book and exhibition Lo que no vemos, lo que nos mira (What We Don’t See, What’s Watching Us), presented at the Amparo Museum in Mexico City in 2014 ().

Figure 22.3

Figure 22.3My works only allow for maintenance, never replacements. What breaks off or disintegrates cannot be brought back through conservation. If I use waste, what interests me is consolidating and arresting as far as possible certain processes of degradation or deterioration. But I cannot go against the passing of time or the lasting nature of some materials. On the other hand, I am also interested in the paradox of the temporal within the constant—for example, how something so ephemeral as burning a sheet of paper makes the paper eternal through the chemical reaction.

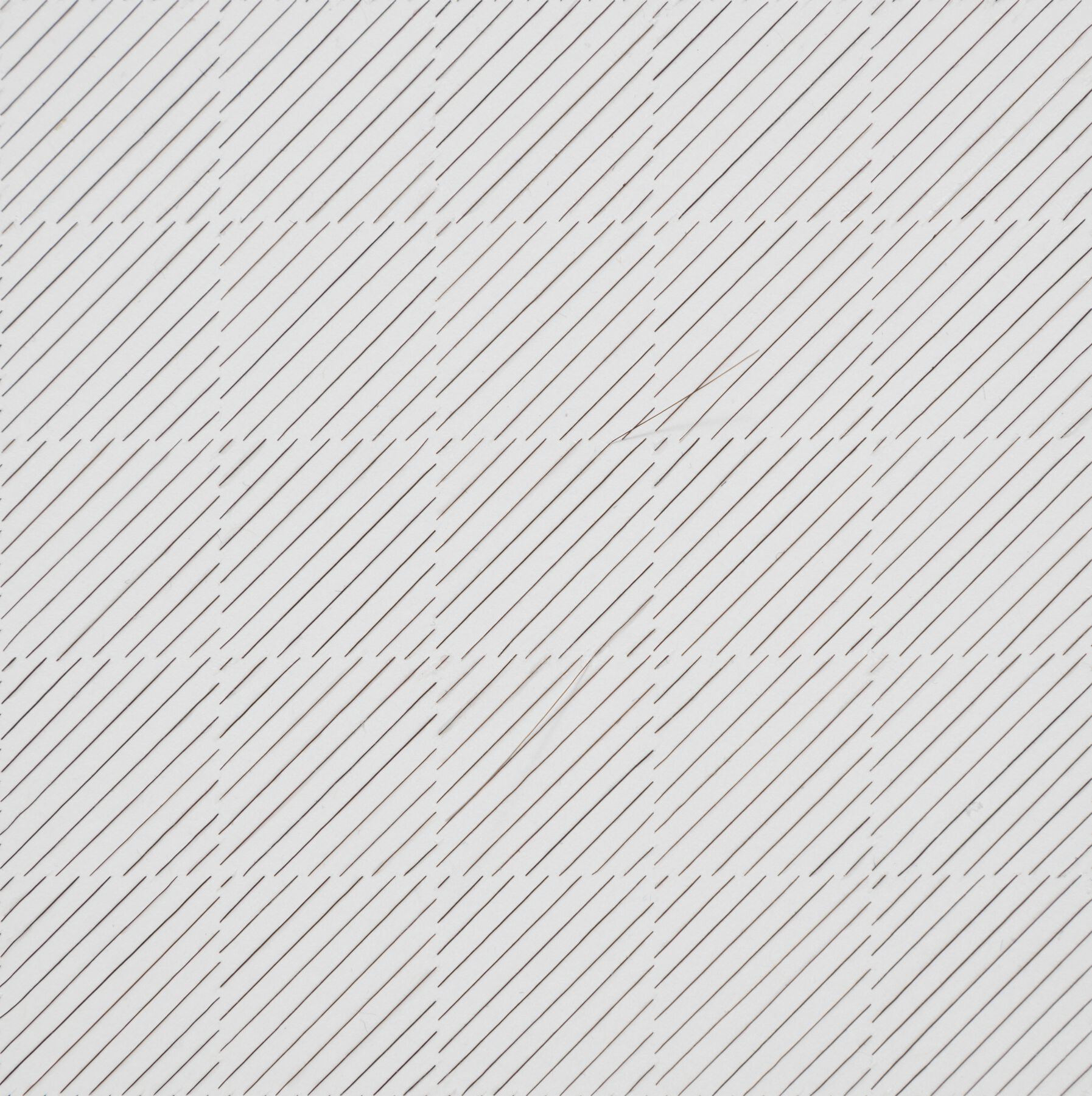

The series of burned papers was, in some way, the start of a phase in my career. I began in October 2007 in Mexico City, simply burning a sheet of white paper (fig. 22.4). The process of transformation was fascinating: seeing a flat, white sheet of paper turn into an irregular, black surface, then the black turns to gray and the paper is destroyed (fig. 22.5). I burned hundreds of sheets of paper until, for some reason, the change from black to gray stopped happening and the last sheet remained burned but intact. With this experiment, I started the series that took me ten years to finally finish in December 2017. It consists of sixteen works in total: forty-three burned papers in various individual groupings—diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs of four, five, and six pieces. Four pieces of this series currently belong to MOCA in Los Angeles, and the rest, which are constituted of the thirty-eight pages of my 2003 MFA thesis, belong to the Pratt Institute in New York. Those thirty-eight pages ended up as eleven pieces in the Pratt Institute because I wanted to respect the number of elements in polyptychs according to the number of pages of each chapter of my thesis. For conservation purposes, all I do to stabilize the ashes of the papers is to apply three layers of aerosol fixative for charcoal drawings to their backs. What is interesting about the series is how I start a process, and all the rest is far beyond my control. This led to several series afterward and, in addition to being some wonderful pieces, they formally and conceptually fulfill my idea of seeking a balance between the formal and the conceptual. The burned papers represent some of the more important pieces in my portfolio as an artist. The adhesives and paper I use are generally acid free, so under normal conditions they should keep well over time. It is important to mention that to date, fifteen years after starting the series, I have not had to conserve any piece.

Figure 22.4

Figure 22.4 Figure 22.5

Figure 22.5After much consideration, I have reached a definition of art as a reflection of the definition of energy in the physics of Lavoisier-Lomonosov, in which the atoms of an object cannot be created or destroyed, but can be moved around and change into different particles. I take it to the field of aesthetic practice and say that art is not created or destroyed; it is only transformed. As an artist I don’t consider myself a painter, a draftsman, or a sculptor, since I feel that reducing art to a single technique is entirely unjust. I believe that art goes beyond that, and that is why I consider myself a crafter of inquiry, experimentation, and exploration: every idea or concept that ends up as a concrete work of art requires specific techniques in which I must try to control the greatest number of variables possible.

My creative space is not just an atelier. When I am in my studio, I regard it as a laboratory more than an artist’s workshop, and I think my body of work is closer to that of a scientist—although there are series in which the hand and the work occupy a greater amount of time.

I use a great diversity of organic and inorganic materials, such as human hair, fingernails, human blood, bird feathers, fish scales, butterfly wings, leaves from various trees (fig. 22.6), tortillas, eggshells, edible materials such as soup noodles, or used elements such as discarded plastic, leather soles of shoes, ceiling tiles from late nineteenth-century homes, sheets of rubber, old aluminum printing plates, and laboratory microscope slides, or countless new (thus canceling the function for which they were created) materials that I gradually collect and classify. Things not being used for any series live in a storeroom as part of my archive.

Figure 22.6

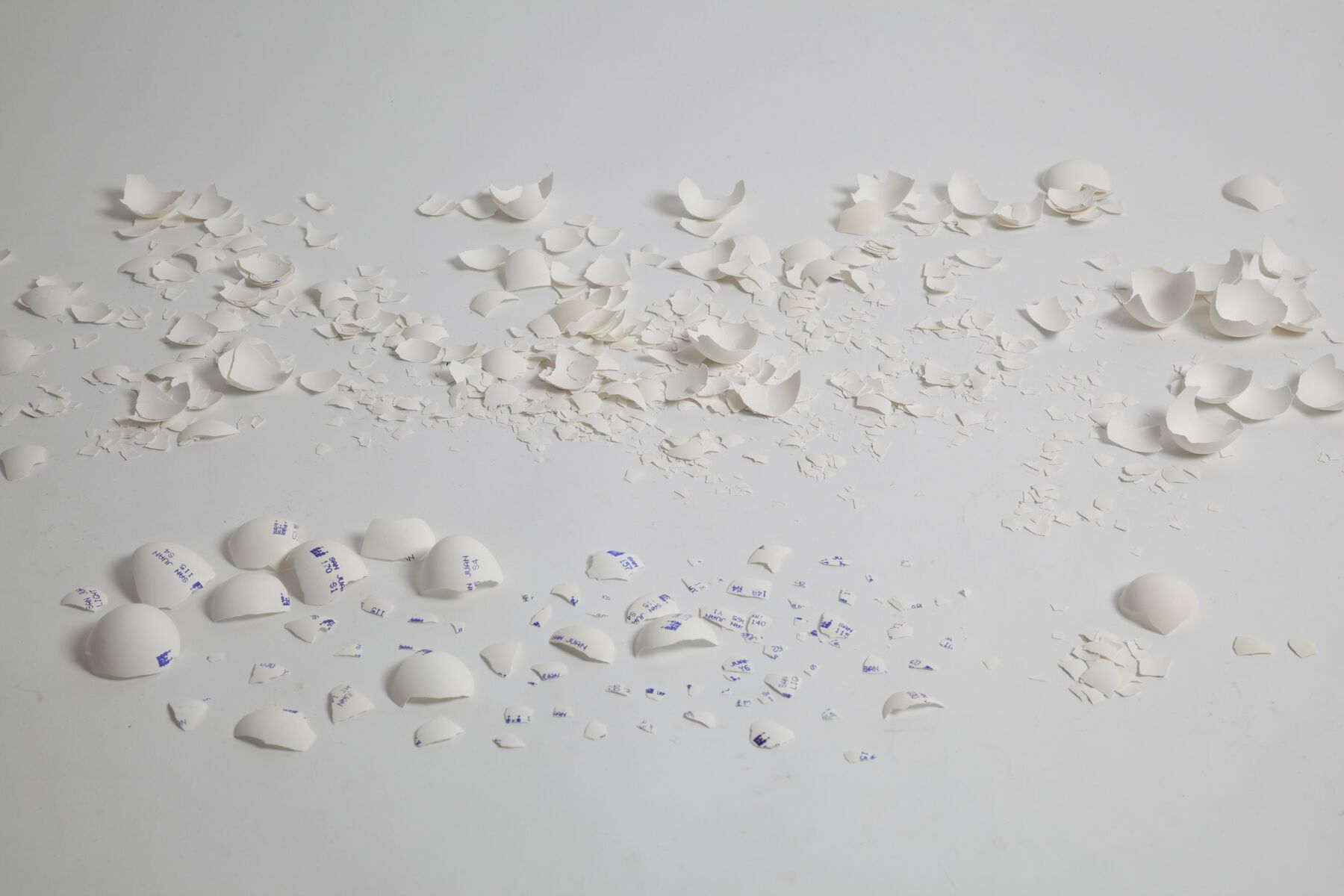

Figure 22.6In my series of drawings on paper with human hair (2004–ongoing, fig. 22.7), although the hair is organic matter, it lasts a very long time as the container of a person’s energy. In the pieces with pigmented turkey feathers (fig. 22.8) and natural-colored feathers from various birds (fig. 22.9), I use acid-free materials, as suggested by conservators. To preserve the color, whether natural or artificial, I enclose them in museum glass, which protects the pieces from 99 percent of ultraviolet rays. If the works lose some color, they are still the same works, just aged over time, which I believe adds something special. The series made with eggshells, titled CaCO3, which I began in 2013 and continues to date, portrays my compulsion to reach degree zero in painting, which has led me to explore the medium itself outside of itself—that is, the idea of painting without painting. The entire surface, prepared with the same care as a canvas that will slowly disappear as it is impregnated with oil paint, will be covered with tiny pieces of this material. The eggshells, previously selected and catalogued by color, are broken up, counted, and placed on the surface so that no empty space is left and, at all costs, they never overlap (fig. 22.10). Control during the process is absolute; I keep a record of the time it takes to cover the entire surface and also how many pieces fit on it. This information provides the title.

Figure 22.7

Figure 22.7 Figure 22.8

Figure 22.8 Figure 22.9

Figure 22.9 Figure 22.10

Figure 22.10Before using any material, I conduct countless tests with advice from conservators, always keeping records and photographs of each exploratory process. All this information is generally requested by the more sophisticated collectors and by institutions or museums before acquiring any work in which the materials may entail some risk for conservation. I believe there are some series within my oeuvre in which the conservator is more like the figure of an alchemist, since they study the materials to be used and provide me with guidelines for the manipulation, work, conservation, and preservation of the elements, so they can be conserved as well as possible for the longest amount of time. What is important is not whether the piece loses commercial value or not, but rather how much it differs from its original state, with changes that differ from those that occur with the passing of time. I think it is important, and to a certain point a great responsibility, that artists receive advice on, or explore the nature of, the materials they use, as well as trying to utilize optimal methods and processes, and materials that can best extend the life of the pieces.

Conclusions

As a young, self-taught artist, I followed a path of experimentation in terms of materials, which led me to learn over the years the importance of the elements constituting each of my pieces. The most important lesson, in addition to an awareness of the material and its futile existence, was the ability I acquired to be always alert to the creation of the pieces, from their conception as an idea to their production, and to keep records of all my processes because, ultimately, it is the life history of each one of them.

Although art is always undergoing change, it is very important that the presence of conservators be a constant in the production of art, particularly in series that involve organic or biological materials. The artist must be always aware of the importance of the formation of his or her pieces, the quality of the materials, the level of risk entailed in the constituent elements, and, above all, the ultimate durability of almost all materials available for the practice of art. Nothing lasts forever, it’s true, but the counsel of experts in matters of conservation can make the difference between an ephemeral piece and one that endures.

This responsibility must also be extended to everyone who works with or owns art, such as collectors and gallery owners, considering that museums, foundations, and centers for specialized studies have much greater expertise in this type of task than any other person involved in the art world. It is well known that some collectors who keep collections of clocks and even wines in the best conditions of humidity, temperature, and movement don’t do the same with their works of art, which may be exposed to direct sunlight, or suffer from incorrect cleaning processes, or any number of risks. A person who acquires a work of art has the responsibility to conserve it in their collection in the best condition possible. The same is true for a gallery owner who handles and safeguards works of art for differing periods of time.

Art is not created or destroyed; it is only transformed.

All will ultimately disappear.

Mexico City, September 2019

Bibliography

- Kautz 2015

- Kautz, Willy, ed. 2015. Lo que no vemos, lo que nos mira. Mexico City: Museo Amparo.